-

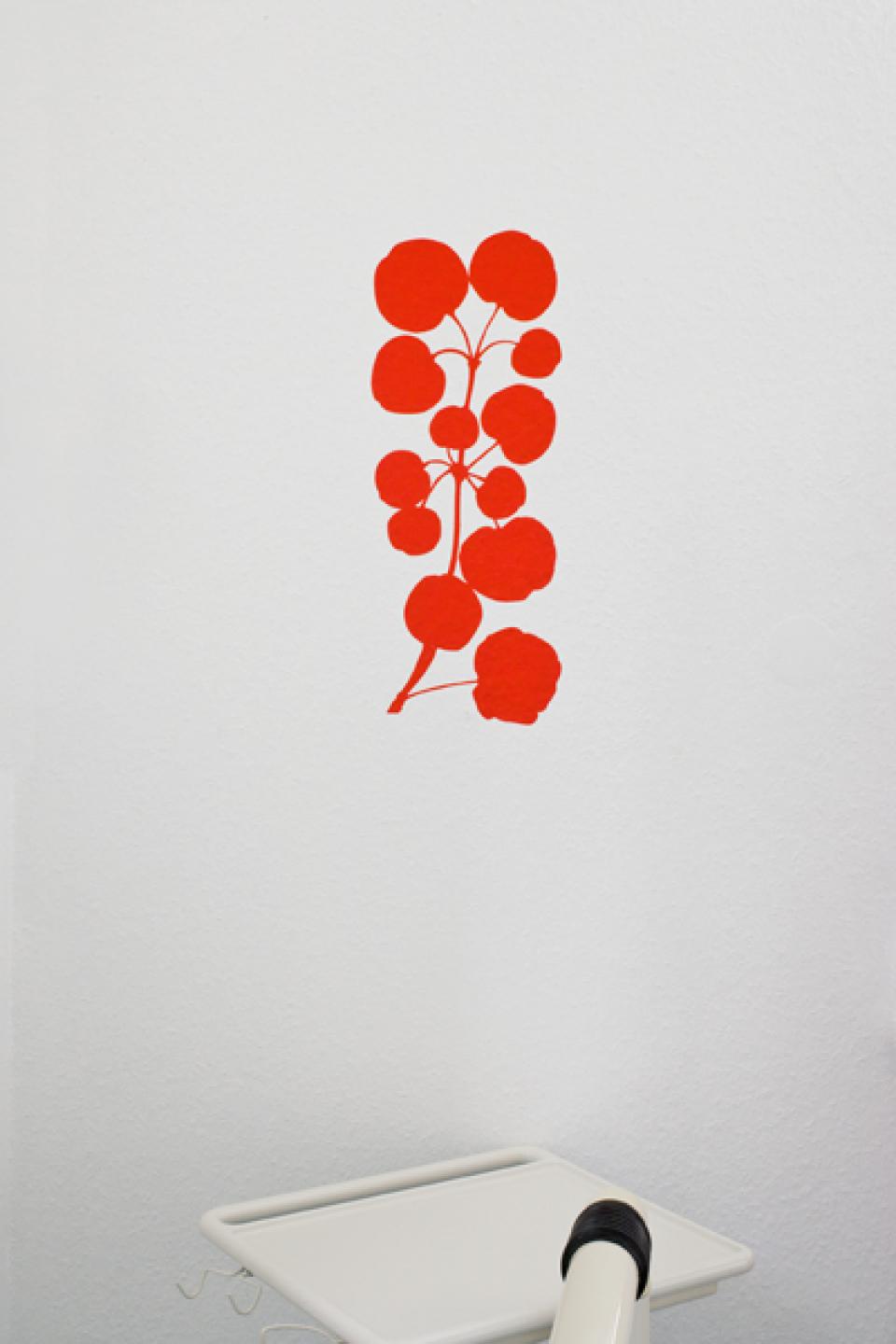

teeth peace 01, 2009

teeth peace

installation in all rooms of a dental practice

vinyl cut on wallpaper / freely based on Philipp Otto Runge

photos: Joachim Fliegner

_____

The installation exists directly on the walls, whereby the architecture, the space - with a wink of irony - becomes part of the artwork.

The wall is therefore not a background scenery, it is the object itself, an equivalent component.

"With her art, Isolde Loock brings natural elements from the exterior into the interior in a very sparing but very poetic and multi-layered way, with the aim of involving these two areas - nature and technology - in a dialogue.

This dialogue, this dialogue, leads from a passive, unreflected view of nature to a closer look and to questions that can creatively break through everyday life in the house, the working routine, and hold a considerable potential of stimulation in themselves."

Dr. Katerina Vatsella -

teeth peace 02, 2009

-

teeth peace 03, 2009

-

teeth peace 04, 2009

-

teeth peace 05, 2009

-

der traum denkt nie an sich 01 / o.T., 2011

„der traum denkt nie an sich“

Studienzentrum für Künstlerpublikationen

8. april - 21. august 2011

WESERBURG Museum für moderne Kunst, Bremen (E)

photos: Joachim Fliegner

___________________

High gloss brochures by Jil Sander, wallpaper pattern books, x-rays, art catalogues, windows and mirrors, newspapers or literary magazines such as Lettre international are edited by Isolde Loock, more precisely inscribed or, to be more precise, associated with her own or other literary texts, such as those by Arthur Rimbaud.

The works described or stamped by hand are based on found materials, because for Isolde Loock the world is full of works and things, there is nothing more to add. Instead of inventing something new, she creates things anew. She gets to the bottom of things, such as fashion brochures, and brings back to normality what has not been achieved, dreamed of or longed for by many, in that the connection with the texts brings about, as it were, a disenchantment of the portrayed. It exposes the illusory world of advertising, which plays with people's dreams.

Isolde Loock has worked very intensively with the most diverse forms of publications, working on existing publications artistically or making her own artist books, postcards, stickers, video editions or multiples and writing poetry books, novels or dream books, in which she has recorded all her dreams for 30 years. Her object poems are associative poems that work from the combination of title and found object, like the work "... immaculate conception" from 100 unprinted picture newspapers.

Dr. Anne Thurmann-Jajes -

der traum denkt nie an sich 02 / o.T., 2011

-

der traum denkt nie an sich 03 / o.T., 2011

-

der traum denkt nie an sich 04 / o.T., 2011

-

der traum denkt nie an sich 05 / o.T., 2011

-

BORN 01, 2011

BORN

performance by the Villa Aurora fountain, Los Angeles, USA

photos: Marie-Louise Korn

In April 2011 "Isolde Loock performed a spring ritual called BORN by the Villa Aurora fountain: She dedicated, with the assistance of two children and our audience, 100 golden spheres - representing the material of perfection, greed and wealth, but also in a significant way symbolizing Los Angeles and the sun - to our fountain filled with water... In this way reflecting on the central importance of water worldwide, but particularly also in a city such as Los Angeles, which is dependent entirely on a complex system of irrigation." (Imogen von Tannenberg, director of the Villa Aurora). -

BORN 02, 2011

-

BORN 03, 2011

-

BORN 05, 2011

-

BORN 04, 2011

-

BORN+ 01, 2012

BORN+

a sculpture and its aging process

;sculpture, Villa Aurora fountain, Los Angeles

Fotos: Craig Havens

Since Isolde Loock´s performance BORN in April 2011 the golden spheres remained in the Villa Aurora fountain, which is now no longer filled with water. They are still keeping their sound... The Los Angeles photographer Craig Havens is documenting;the progressive changes that will occur with Isolde Loock´s sculpture BORN+ as it ages. Meanwhile the;Composer-in-Residence Michael Maierhof used the golden balls for a video/composition. -

BORN+ 02, 2012

-

BORN+ 03, 2012

-

BORN+ 04, 2012

-

BORN+ 05, 2012

-

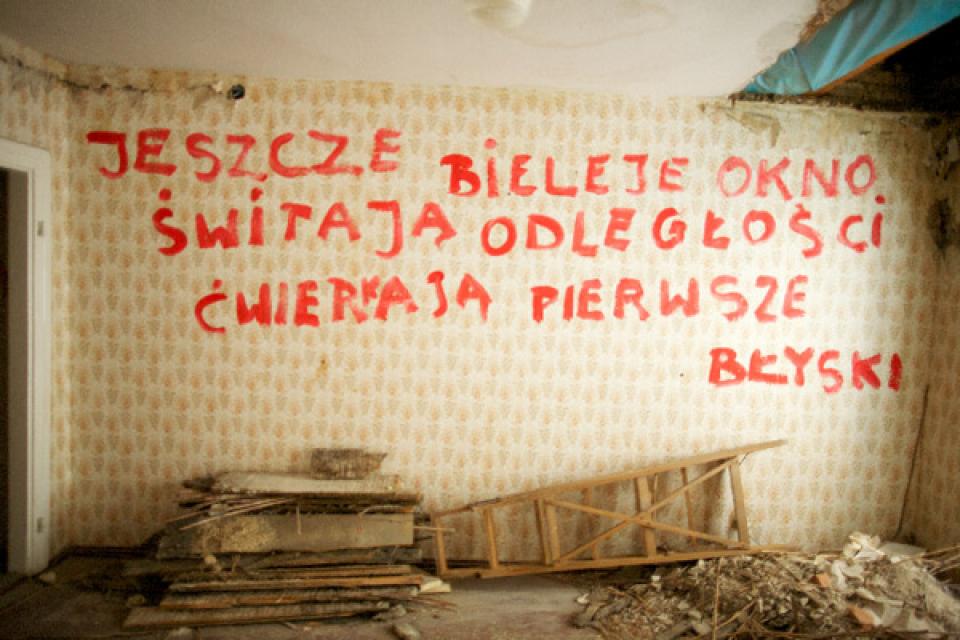

Uffm Kreuz 01, 2011

Uffm Kreuz - Wegbeschreibung (How to get there)

installation on the occasion of the Day of the Open Monument in Görlitz, „Kunstreich Görlitz zeigt“

photos: bangbang

Isolde Loock takes you on a literal guided tour through the listed nested Görlitzer Hallenhaus Weberstraße 4 built in 1488. First the house belonged to a painter. Since 1675 it was a baker's house, whose owners were called the Kreuzbäcker.

From the cellar to the roof, words run along walls and ceilings: language that appears to be a useful means of communication but does not live up to its promises.

Based on poems by the Polish poet Wislawa Szymborska, the German and Polish sentences each form their own language spaces, which interact with each other and with the visitors.

Precious from language, written directly on rough plaster or torn wallpaper remains. -

Uffm Kreuz 02, 2011

-

Uffm Kreuz 03, 2011

-

Uffm Kreuz 04, 2011

-

Uffm Kreuz 05, 2011

-

Der Schutzhase oder die Meisterlampe 01, 2001

Der Schutzhase oder die Meisterlampe

project Schuricht-Bau, Bremen

photos: Joachim Fliegner

Bremen artist Isolde Loock has taken on the exciting task of developing an artistic overall concept for a new building.

Isolde Loock moves with most of her works in the field of new media. She works with actions, with video films and video installations, with computers, with text, with typography, with newly developed and found material - these can be objects, x-rays or photographs, but they can also be words and signs.

When she saw this building for the first time, she noticed the transparency of the architecture as an important aspect. The glass lends the building lightness and allows a practically permanent view of nature from the outside. This transparency also attracted her attention inside the building, as an open structure of the spacious offices with their glass views, a structure that is intended to promote communication.

This fact was very helpful to the artist. Isolde Loock's work has to do with communication in the broadest sense. In this case, she developed a dialogical concept based on the tension between the nature that surrounds the house and the technology that is traded in the house.

With her art, she brings natural elements from the exterior into the interior in a very sparing but very poetic and multi-layered way, with the aim of involving these two areas - nature and technology - in a dialogue.

This dialogue, this dialogue, leads from a passive, unreflected view of nature to a closer look and to questions that can creatively break through everyday life in the house, the working routine, and hold a considerable potential of stimulation.

The picture at the entrance is the focal point of the concept. When you stand in front of the light box, you will see a long brown, earth-colored shape above a bright pinkish-green iridescent surface. It extends into the width like a landscape representation and, for example, is reminiscent of an excavated deepening of the earth in a meadow, on a field.

When taking a closer look, however, it quickly becomes apparent that the brown form is a coat. And if you position it correctly (very close to the left edge of the lightbox), you can see that this is actually the image of a rabbit drawn into the width, as the title of the image "Schutzhase" already reveals.

She used one of the most famous hare pictures as a model, namely "The Little Rabbit" by Albrecht Dürer, painted in 1502.

With Dürer's rabbit, Isolde Loock brings a piece of nature into the interior of the house that is rich in symbolic content. The hare has always been regarded as a symbol of fertility and prosperity, of speed, with its extended hind legs, which by the way allow it the paradox of being able to run uphill faster than downhill. "If that's not a good motif for an up-and-coming company," says Isolde Loock.

But also other of its characteristics make the hare a suitable "protection animal" for the company. The rabbit is considered to be clever, he is a very watchful observer of whom it is said that he even sleeps with his eyes open, and with his soft fur he stands for warmth and security. At La Fontaine and in German fables, the rabbit is the clever advisor: Meister Lampe. In recent art history, a dead rabbit has also become famous, to which Joseph Beuys dedicated one of his actions. And Dieter Roth's "Scheisshasen", made of rabbit dung, are also frequently found as multiples.

Albrecht Dürer's painting on the threshold of the modern world, after the Middle Ages, has almost become a parable for the scientific interest in the research object nature because of the incredible precision of his observation and representation of nature.

Isolde Loock also conducts research in other fields, namely in the field of painting itself and that of language. She calls the process according to which she realizes images like the "Schutzhase" stretching. She always uses pictorial motifs from art history as models for her stretchings, mostly motifs that are generally known through reproductions, such as Dürer's Hase here, but also from pictures by other great masters such as Liebermann, Courbet or Cézanne.

In Renaissance painting, the so-called anamorphoses distorted the perspective of the real object in the picture and thus deprived it of immediate recognition. Isolde Loock now distorts the painting itself with today's technique. The motifs are torn apart, almost dissected, by pulling them apart and stretching them on the computer. Isolde Loock analyzes them in their own way and expands them with additional levels of meaning.

In these pictures, she involves the viewer, because the original motif, her model, can only be discovered through movement of one's own, by positioning oneself in the right place.

This involvement of the viewer, the interaction, is an important aspect of communication in Isolde Loock's work. It becomes clear as an artistic process especially in the second part of the concept.

This second part consists of stylised, computer-processed natural elements from the North German flora and fauna being placed in many different places in the house. They run like a mental thread through the whole house. And that is - following the idea of transparency, which was already hinted at with the light box at the entrance - on window panes, on separating panes and on mirrors.

On the ground floor there are motifs from the plant world, on the first floor insects, butterflies and beetles, on the second floor birds.

Isolde Loock's interest in language, in the pictorial quality and ambiguity of language, comes to the fore. In this context, it can be recalled that Isolde Loock came to the visual arts through literature. She has remained true to her love of language. This can be seen wonderfully in her selection of possible plant names. Her list includes the following plants, all with ambiguous names:

Dandelion, crow's foot, forget-me-not, nightshade, speedwell, blood eye, thimble, thousand grain, duck lens, heart harness, frog spoon.

It looks similarly ambiguous with the birds:

Nightjar, Swampfinch, Starling, Wren, Blackcap, Yellow Warbler, Goldencrest, Willow Warbler, etc.

So the names alone already trigger many associations that lead beyond what is depicted or described.

Isolde Loock has often carried out such communication projects, for example in various cities: in Kassel, New York, Frankfurt and Bremen, where she stuck „Eingeschweisste Sätze auf Strassenpflaster“ („Sie wissen ganz genau, dass die Welt heute andere Probleme hat, als Sein oder Nichtsein“),

in the "Communication-Service" 1999, in the project Oreste at the Venice Biennale, with the "Body guard" campaign at Expo 2000, or with the "Herzkammer-Projekt" in the Galerie im Park in Bremen Ost, 2001.

Dr. Katerina Vatsella -

Der Schutzhase oder die Meisterlampe 02, 2001

-

Der Schutzhase oder die Meisterlampe 03, 2001

-

Der Schutzhase oder die Meisterlampe 04, 2001

-

Der Schutzhase oder die Meisterlampe 05, 2001